I have one living grandparent—my father’s mother, who’s 89.

Nana.

I visited Nana recently and went through the usual activities—talking about myself in a loud voice, fixing her “broken machine” by unminimizing the internet browser window, being told to slow down Timothy and get in the left lane, even though the turn is still a half mile ahead. But I also used the visit as an opportunity to do something I have not done nearly enough in my life—ask her questions about our family.

I don’t know you, but I can almost guarantee that you don’t ask your grandparents (or older parents) enough questions about their lives and the lives of their parents. We’re all incredibly self-absorbed, and in being so, we forget to care about the context of the lives we’re so immersed in. We can use google to learn anything we want about world history and our country’s history, but our own personal history—which we really should know quite well—can only be accessed by asking questions.

During my visit, Nana referred to herself as “the last of the Mohicans,” meaning basically everyone she spent her life with is dead—her husband, siblings, cousins, and friends are all gone. Besides that being the most depressing fact of all time, it was also a jarring wake-up call that a treasure trove of rich and detailed information about my family’s past exists in one and only one place—an 89-year-old brain—and if I kept dicking around, most of that information would be lost forever.

So on this visit, I started asking questions.

She was annoyed.

But it only took a couple minutes for her to become absorbed in storytelling, and I spent the next three hours riveted.

I learned more than I had ever known about her childhood. I knew she and my grandfather had grown up during the Great Depression, but I never really knew the unbelievable details—things like her seeing a mother and her children being thrown onto the sidewalk by their landlord and left there to starve and freeze until every neighbor on the block chipped in a coin or two from their own impoverished situation so the woman could rent a room for one more month.

I learned a ton about my four paternal great-grandparents—again, I had known the basic info about them, but it was the details that for the first time made them real people. Three of them grew up in rough New York orphanages—the fourth left everything she knew in Latvia in her mid-teens and took a boat alone across the Atlantic, arriving in New York to work in a sweatshop.

I even for the first time heard stories about my grandmother’s grandmother, who came over separately from Latvia and lived with the family for her last years—and apparently had quite the personality. Thankfully, she died in 1941, just months before she would have learned that her four sons (who unlike their mother and sister, stayed in Latvia because they had a thriving family business there) were all killed in the Holocaust.

I knew none of this. How did I just learn now that my great-grandmother’s four brothers died in the Holocaust? And now that, for the first time, I know my four paternal great-grandparents and great-great grandmother as real, complex people with distinct personalities, I cannot believe I spent my life up to now satisfied with knowing almost nothing about them. Especially since it’s their particular orphanage/sweatshop/Great Depression struggle that has led to my ridiculously pleasant life.

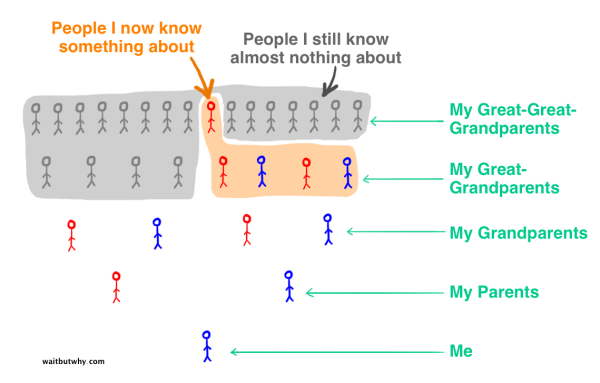

And as happy as I am that I at least scratched the surface of learning who these people were, I’m now sad about all of these other gray people:

All of this has gotten me thinking about genealogy and how fascinating it is as a concept. What happens if I just keep extending my family tree up and up and up? What exactly is a fourth cousin and how many of them do I have and where are they all right now? How weird is it that to some kid in 2300, I’m one of the old-fashioned-looking dudes really high in his family tree on a level with hundreds of others? Normally, I’d just go internet spiral about this on my own, but since Wait But Why exists, we’re gonna do it together—

The Past: Your Ancestor Cone

So let’s start with the past, and see what happens if we keep going up the family tree, or what I’ll call your Ancestor Cone:

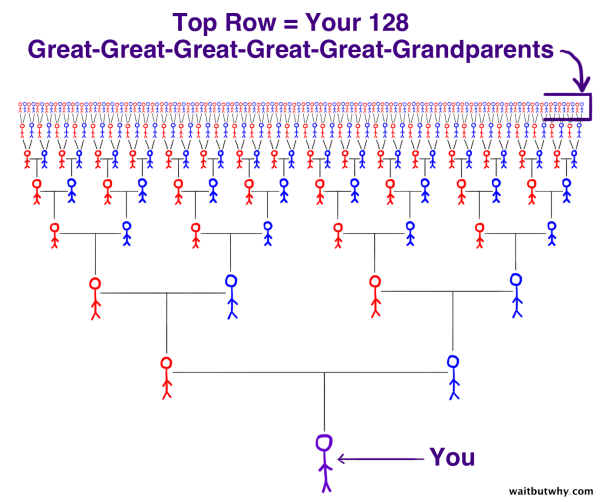

You can see that things get hectic pretty quickly when you start moving back generations. The top row is the 128-person group of your great5 grandparents, or your grandparents’ grandparents’ great-grandparents. The thing that I find surprising is how recently in time you had such a large number of ancestors. Estimating an average generation at 25-30 years, most of those people were your current age around 1800-1825. So the early 19th-century world contained 128 random strangers going about their lives, each of whose genes makes up 1/128th of who you are today.

Who were they all? What countries did they live in? What did they all do with their lives? What tragedies did they endure and what were their greatest triumphs? What were the 254 parent-child relationships in this diagram like? Which of the 252 in-law relationships above were close and loving and which were angry and contentious?

The craziest thing to me is that this diagram, which only represents the last 200 years of your ancestry, contains 127 romantic relationships, each involving at least one critical sex moment and most of them probably involving deep love. You’re the product of 127 romances, just in the last 200 years alone.

Alright, I’m nervous about this, but I’m gonna take a crack at going back even further—

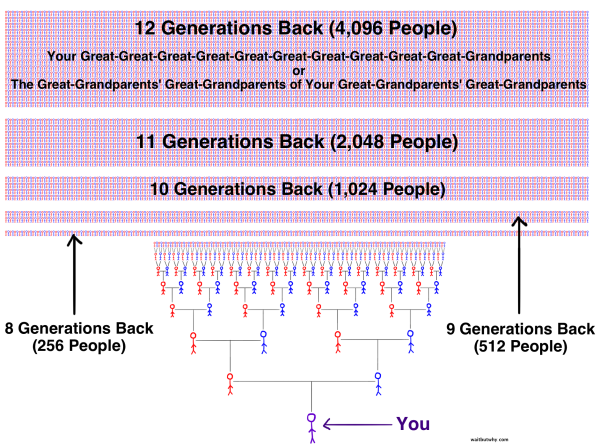

Okay that got completely out of hand. This diagram only goes five generations farther back than the one above it and look at the insanity that took place.

The 4,096 human beings in the top section are your great10 grandparents. Most of them were your age in the second half of the 1600s, just as the Enlightenment was getting going in Europe.

You can see why it’s not really that impressive when someone tells you they are descended from famous royalty who lived a few hundred years ago. Look how many people you’re descended from only about 300 years back! Within that top section, there’s probably some royalty, in addition to some peasants, scholars, warriors, painters, prostitutes, murderers, lunatics, and any other kind of person who existed back then.

Finally, I know I already made this point in the evolution post, but look closely at that top section and notice that you can actually see 4,096 distinct tiny people in there—and realize that if you pluck just one of them from there, you would not exist today. Come on.

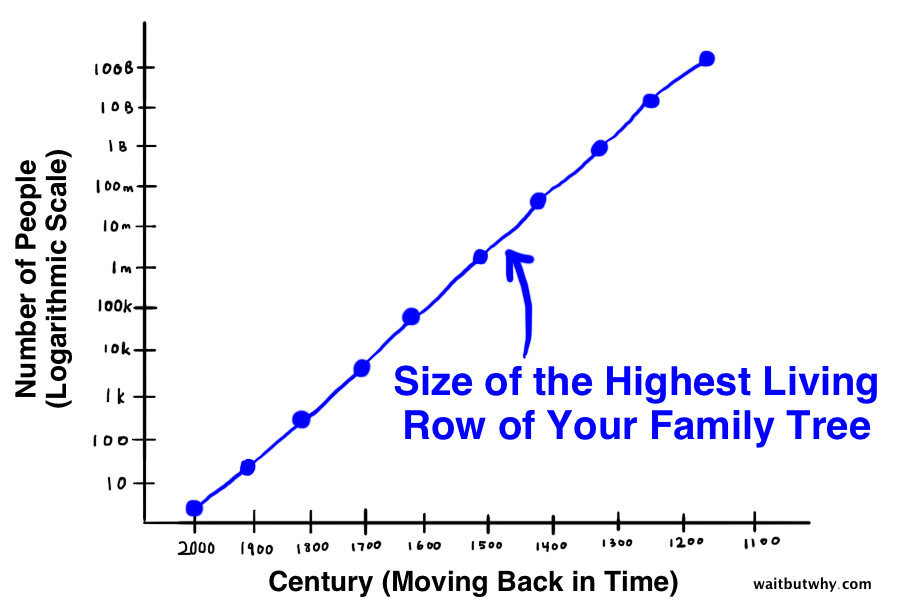

You may also be noticing that there’s something that doesn’t make sense about the way these numbers are zooming up exponentially—we’re at 4,096 going back three centuries, and continuing at that rate, our ancestor number goes like this:

That puts you at 68 billion ancestors around 1100 AD. The reason that’s problematic is that the world population goes like this:

So how do we explain this?

With a concept called pedigree collapse, which is what happens when people end up with a mate who is somewhat or very closely related to them. So for example, if two cousins had a child, that child would only have six great-grandparents, not eight. Or, to put it another way, there are eight filled great-grandparent spots on that child’s family tree, but two of the spots are duplicates of two other spots—

Before you wince, absorb this fact: according to Rutgers anthropology professor Robin Fox, 80% of all marriages in history have been between second cousins or closer.1

The reason for this is that for most of human history, people spent most of their lives in the same five mile radius, and the other people in that same area tended to be immediate and extended family. To get away from their extended family when courting, men would have to walk over five miles away, which after a long day of hunting you just don’t feel like doing.

In the Western World, this is largely a phenomenon of the past, but in many parts of the world, this is still a common practice—for example, in most of the Middle East and North Africa, over 50% of today’s marriages are between second cousins or closer.2

So that group of 4,096 people above? A number of those spots are undoubtedly duplicates, meaning the real number of distinct people is likely a bit lower—and for someone a few thousand years ago, the number of 10th generation ancestors they’d have would be a lot lower than 4,096.

Because of pedigree collapse, if you extended your family tree way, way back, it would begin to get smaller, resulting in a diamond shape:

The widest point of the Ancestor Cone happens for most of us around 1200AD,3 when our family tree is near the total world population at the time. From that point on, pedigree collapse becomes a stronger factor than the normal upward x2 multiplier, and the tree converges inwards.

The Present: Your Living Relatives

So in this frenzy of procreation we’re all a part of, what’s the deal with our relation to the other people on this Earth today?

The simplest way to think about it is that every stranger in the world is a cousin of yours, and the only question is how distant a cousin they are. The degree of cousin (first, second, etc.) is just a way of referring to how far you have to go back before you get to a common ancestor. For first cousins, you only have to go back two generations to hit your common grandparents. For second cousins, you have to go back three generations to your common great-grandparents. For fifth cousins, you’d have to go back six generations until you arrive at your common pair of great-great-great-great-grandparents.

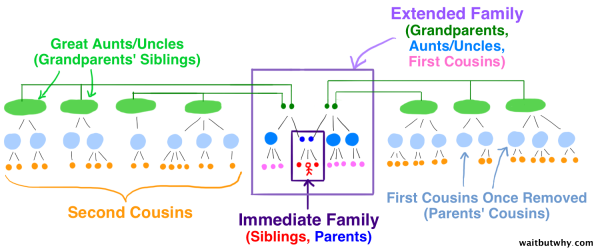

Since a lot of people get confused about cousin definitions, I made a little chart illustrating what a second cousin is.

So notice that for you and your second cousin, A) your parent is a first cousin of their parent, B) you have grandparents that are siblings, and C) their parents are your common great-grandparents. For third cousins, everything just goes up a level—your parents are second cousins, your grandparents are first cousins, your great-grandparents are siblings, and you have a common pair of great-great-grandparents.

(For the whole “once/twice removed” thing, it’s about being on different generations—so your second cousin’s child is your second cousin once removed, because it’s one generation away from you; your grandfather’s first cousin is your first cousin twice removed. A straight second, third, or fourth cousin must be on your same generation level.)

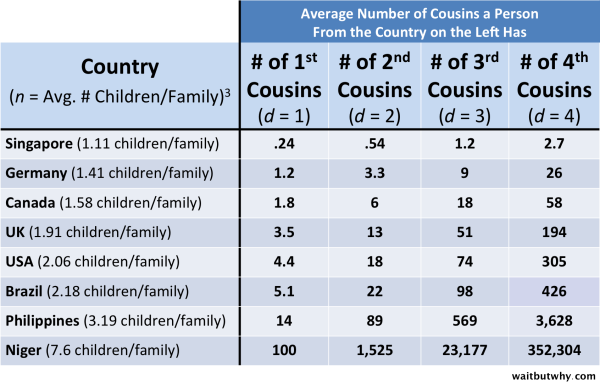

The number of cousins you have grows exponentially as the degree of distance goes up. You may have a small number of first cousins, but you likely have hundreds of third cousins, thousands of fifth cousins, and over a million eighth cousins.

Because I got a little obsessed with this concept while doing this post, I decided to roll up the nerd sleeves and figured out a formula for this:

(n-1) 2d nd

—where n is the average number of children being had by a family and d is the degree of cousin you want to find the total number of (an explanation for this formula is at the bottom of the post). (P.S. I’m thrilled with myself right now.) (But also scared because there might be a better way to do this, so feel free to add suggestions in the comments.)

So to find out how many third cousins you’d have (d=3) if your family averaged having two children per couple (n=2), it would be (2-1) 23 * 23 = 64.

The number of fourth cousins you’d have (d=4) if your family averaged three children per couple (n=3) would be (3-1) 24 * 34 = 2,592.

Using this formula on yourself is hard, because you don’t know n, the average number of children your extended family is having—but you can get a general ballpark for the number using your nation’s average number of children per family statistic. I calculated some examples below:

Most interesting to me is that these numbers go up so exponentially that taking the world average for number of children per family (2.36)4, you can use the formula to calculate that if breeding were mixed evenly across cultures and nations, the most distant relative you’d have on Earth would be a 15th cousin.

However, since breeding isn’t mixed evenly and is instead contained mostly within nations and cultures, the most distant person within your culture or ethnicity is probably closer to you than a 15th cousin, while the farthest relation you have on Earth is likely to be as far as a 50th cousin.5

In any case, you have hundreds if not thousands of third and fourth cousins and you’re probably friends with some of them without realizing it—you might even be dating one of them.

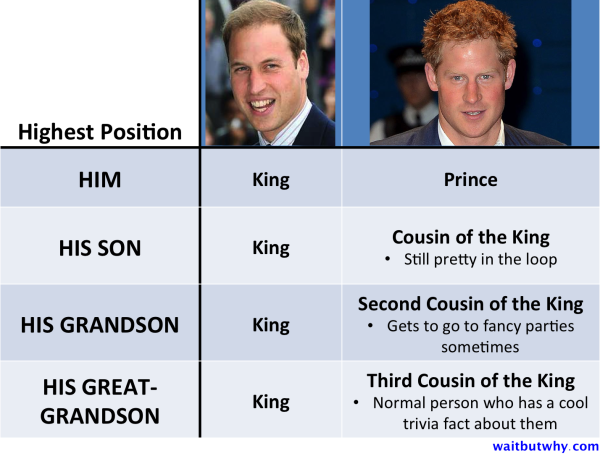

The other way to look at this is from the top down and see how quickly the distance of relation is magnified as generations move down—while you and your sibling grew up in the same house, your kids will be cousins who might or might not be friends and your grandkids might barely know each other. When it comes to your and your sibling’s great-grandkids, it’s likely they won’t ever meet, and your great-great-grandkids might be best friends with each other and will never realize that their great-great-grandparents were siblings.

A nice example of this phenomenon:

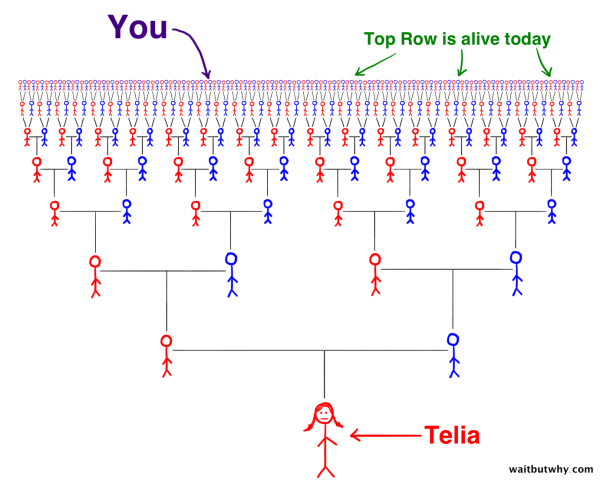

The Future: Your Descendant Cone

Maybe you won’t have children, or maybe your children won’t have children. But barring those possibilities, you’re likely to end up being either the great patriarch or matriarch of a Descendant Cone that will eventually make up a sizable chunk of the human race. In its first couple hundred years, before expanding into the thousands, it might look something like this:

Let’s take a closer look at one of your hundreds of great-great-great-great-great-grandchildren:

Little Telia, born right around the year 2300, is as much a mystery to you as your ancestors from the early 1800s up above. She owes her life to you, and somewhere in her personality is a trait or two of yours—but that’s the extent of your connection.

Party’s Over

Now so far in this post, you’ve gotten to enjoy being featured as the key person in all the family trees we’ve drawn. You’ve been the child that thousands of romances have aligned perfectly together to produce. You’ve been the centerpiece of a large extended family with rings of siblings and cousins around you. And now, you’re the great founder of a vast cone of descendants.

But all you have to do is shift the perspective, and suddenly you’re one of some 17th Century guy’s ten thousand descendants; you’re the second, or third, or fourth cousin (it’s weird to think of yourself as just someone’s random second cousin); and to Telia, you’re no grand patriarch or matriarch—you’re an unbelievably random tiny stick figure high up on her Ancestor Cone and you’re fuzzy because Tim can’t figure out how to export high-resolution images from Pixelmator even though he tried a bunch of different things:

Most of those people on the top line are alive today, and you have no idea who’s standing there on Telia’s top line with you—that guy who works at the coffee shop might be her great-great-great-great-great-grandparent too, the two of you just two of her hundreds of nameless, forgotten ancient ancestors.

Conclusions

- Now I feel special and important and also I feel irrelevant and meaningless.

- Writing this post has really hammered home the point that humans are mainly a temporary container for their genes. In 150 years, all 7,100,000,000 people alive today will be dead, but all of our genes will be doing just fine, living in other people.

- After the first conclusion point, I was teetering on whether to feel good or bad about all of this. Then, I depressed the shit out of myself with the second point. But to throw my moping ego a bone, I’ll consider an interesting idea, that my descendants might not need to ask their Nana questions to learn about my life and get to know me a bit—technology changes everything. In 100 years, my great-great-grandson might be able to easily pull up all kinds of info/photos/videos and learn whatever he wants to, which I’m sure will be nothing because the last thing he’ll be thinking about is what his great-great-grandfather was like. Dammit.

- In any case, for now, there’s really only one good way to learn about where you came from—so start asking.

_______

If you like Wait But Why, sign up for our email list and we’ll send you new posts when they come out.

To support Wait But Why, visit our Patreon page.

___________

Other WBW Posts That Put Your Life in Perspective:

Meet Your Ancestors (All of Them)

Explanation of the Cousin Calculation Formula

The formula is (n-1) 2d nd

—where n is the average number of children being had by a family and d is the degree of cousin you want to find the total number of.

It boils down to a simple multiplication of the number of top-level siblings [(n-1) 2d] times the number of “eventual offspring on your generation level” each of those top-level siblings ultimately produces (nd).

Example 1

For a first cousin, the “top-level” is one’s parents’ generation because that’s the generation where we move “sideways” in the family tree before heading “down” to the first cousins. In this example, the number of “top-level siblings” is the number of blood-related aunts and uncles one has, or the number of combined siblings of one’s parents. We get that number by multiplying the total number of children in an average family minus one (that will get us the number of siblings since subtracting the one removes the parent) times the number of our top-level ancestors we need siblings for (in this case, two, since there are two parents). So for a first cousin calculation, the number of top-level siblings if the average family has three children (n = 3) is (3 – 1) * 21, or two siblings times two parents, equals four top-level siblings.

The second part is figuring out how many eventual first cousins each top-level sibling will produce. Since we’re using an average number of children in a family, culture, or nation as a constant n, we just need to multiply each top-level sibling by n to get their number of children. Since their children will have the same number of children n, to go down two generations we would multiply the top-level siblings by n2—this can be simplified as nd. For first cousins, we’d just need to multiply by n once because we’re just going down one generation.

So to get the number of first cousins in a family that always has three kids, d=1 and n=3, and (n-1) 2d nd comes out to 4 x 3 = 12. This is correct because your parents have four combined siblings and each has three kids.

Example 2

To find the number of third cousins someone has if everyone has two kids, we make n=2 and d=3. Here, the top-level siblings are on the great-grandparent level, because it’s their siblings whose great-grandkids are your third cousins—it’s on the great-grandparent level that we move sideways and then down to get to our third cousins.

So the number of great-grandparent siblings here is (n-1) 2d = (2-1) 23 = 8. This makes sense because you have eight great-grandparents and each one has one sibling (since in this example everyone has two kids, or one sibling). Each great-grandparent has nd = 23 = 8 great-grandchildren (since we’re moving four generations down and having two kids at each step), so the total number of third cousins in this example is 8 x 8 = 64.

______

Sources

Richard Conniff. “Go Ahead, Kiss Your Cousin.”

The Straight Dope: 2, 4, 8, 16, … how can you always have MORE ancestors as you go back in time?

NationMaster Fertility Rate by Country

John E. Pattison (2007), Estimating Inbreeding in Large Semi-isolated Populations: Effects of Varying Generation Length and of Migration, American Journal of Human Biology 19(4):495-510

The chapter All Africa and her progenies in Dawkins, Richard (1995). River Out of Eden.